When Harry Met Wall Street

After getting tangled up in two botched corporate finance transactions, Transpetrol, the majority holder of Benor Tankers, took the company private on its tenth birthday. Since Benor was one of the first non-family controlled tanker companies to go public in Oslo, we think that the loss of the company as a public vehicle deserves some reflection.

The first nine years of Benor’s public life were relatively uneventful. The company did its initial listing in Bermuda in January 1990 followed quickly by a listing in Oslo the next year and then went about the business of transporting oil. Like all shipping companies, Benor bumped its way through rough market conditions, energetically raising capital in the bank market and through secondary equity offerings.

Continue Reading

The Evolution of Allied Maritime, Inc.

By Kevin Oates

Ask a charterer or a charterers broker when he is in most demand and invariably he will say when the shipping market is bad. This is because in a strong market owners can more easily find profitable employment for their ships and whether one gets market rates or higher is largely irrelevant because people are making money and that makes the happy.

In a weak market, not only do cargoes become scarce, but rogue charterers emerge tempting owners with above market rates that will never be paid. Compounding the already difficult situation, poor market conditions generally slow down the payment cycles of shippers, charterers and receivers and there are often long delays in the payment of freight and demurrage. As a result, a good charterer, or charterers broker, who performs and efficiently employs ships is normally in great demand.

Looking at this relationship schematically, it could be argued that the chartering cycle is a mirror reflection of the shipping cycle. While the peaks and troughs of the chartering cycle do not match those of the shipping cycle, a case can be made that if one were involved in both chartering and owning, the cycles would compliment each other and the consolidated performance would be stronger.

Continue Reading

PEAK PEEKING

Part 2 of a 2 part series

By Geoff Uttmark

Maxima and minima may provide drama, but fortunes are made or forgone at the inflection points. Missing a market turn does not mean taking to the boats, if the right options are in place.

Think figuratively! It’s the only way to make sense / cents of shipping. Take, for instance, the superlative “Ships are the biggest machines on earth.” True enough, so long as “earth” is taken figuratively. Again, consider trading ships. Not the routine day-in, day-out business of transporting cargoes in them that comes to most minds, but actually buying and selling ships themselves. It’s a game of figuring among giant trading houses, aristocrat owners, merchant captains and daring wanabees that combines information, intuition, courage and capital. “It’s in the blood,” say the Greeks, and they should know. But has another kind of figuring, i.e. cold-blooded arithmetic – or more precisely, calculus, entered the when to buy or sell equation? For those who know the difference between transporting raw materials and transforming raw data such as shown in Figure 1, the signs are there that the recent spate of deliveries to owners who had rarely, if ever, committed to newbuildings in the past might have been more than coincidence or herd instinct. Continue Reading

Dead cat bounce or real recovery? The outlook for containership values and time charter rates.

This paper was presented at the Marine Money “Ship Finance 2000″ conference held in New York on the 20th June 2000, by George Hulse, Managing Director of Howe Robinson Sales & Purchase.

Introduction

‘Marine Money’ – Now there’s a thought to conjure with! Recent studies have shown that returns on capital in the dry bulk markets have averaged between 2-6% over the last decade. However, before anybody considers changing the name to ‘Marine No Money’, you might like to know that investment in the containership market has, on average, generated returns on capital in the region of 3-5% above those of the dry bulk sector and is on its way up. In the last 15 months average charter earnings for containerships have increased by 55% and asset values are up 35%. And importantly the outlook for containerships continues to be firm. This, in effect, is a wake up call!

This paper will address the following:

- review the development of the containership fleet

- consider the market for containerships

- analyse the implications of the changing ownership of the fleet

- and finally, answer the questions initially posed by the conference organizers

Continue Reading

Is there a brave bank out there?

by Kevin Oates

It happens with everything from tankers to tech stocks, investors follow a mob mentality and tend to over buy and over sell. In our view, this is precisely the case with lending to smaller owners. Banks have made a herd-like push to follow only corporate credits to find that there are not that many, and the ones that are demand sub-hurdle pricing. As a result, we think there may be a terrific opportunity to bank smaller owners with lower geared loans and larger owners with mezzanine finance. In either case, risk and reward might find themselves in harmony.

MOMENTUM

During May and June 2000, to coincide with Posidonia, many shipping publications issued articles and surveys showing the momentum in Greek shipping over the past 12 months. The issues covered ranged from the number of Greek shipowners ordering newbuilds, to the number of secondhand vessels acquired during the first five months of the year to the record amount of financing emanating from top Greek and international banks. It certainly appears as if Greek shipping is going from strength to strength and that the financial community is there to support it.

Continue Reading

Equities – July 2000

Equities – July 2000 Continue Reading

STRUCTURING SOLUTIONS FOR TANKER CHARTERERS, OWNERS AND FINANCIERS

By Peter M Swift, Director, Seascope Shipping Limited

Ship Finance 2000, Marine Money Conference, New York

Management of Risk – operational, reputational, commercial and financial – is the prime consideration of the principal participants in shipping today. This is certainly the case in the oil and gas sectors, on which this paper is mainly focussed: the objective of this paper being to provide a few comments on the structuring of the arrangements between charterers and owners and in passing the potential “bankability” of those arrangements.

Other speakers in the session are also addressing changes in the tanker and gas markets, the requirements and expectation of owners and charterers, the structuring and financing of transactions, and industry responses to these challenges. My observations will therefore hopefully complement theirs, others may well repeat some their views, and any that are at variance will no doubt be challenged.

Continue Reading

PEAK PEEKING: Topless Might Impress at the Beach but Valley Viewing Also Has Rewards

Part 1 of a 2-part series

By Geoff Uttmark

Q. Why is spotting market tops in shipping a lot like living in Seattle?

A. You’re sure that majestic Mount Rainier is out there somewhere, but it’s so cloudy most of the time you can’t tell where it is, let alone how high it is.

Though there are notable exceptions, shipping is most often described as a derivative industry. Demand for marine transport is driven by the level of activity in industries that require it. By extension, shipbuilding is a derivative industry of shipping. More ships are ordered when demand for seaborne transport is high. That’s when freight rates are putting sufficient cash in the pockets of optimistic owners to enable them to renew and expand their fleets. Predictably, of course, hot shipping markets cool off. Freight rates fall, ordered ships become delivered ships, and depressed conditions become outright depressions. As a result, over-leveraged shipping companies restructure, if they are able, over-age tonnage goes to the breakers, and overall industry consolation is spelled “consolidation”. Continue Reading

WHAT NOW FOR OSPREY?

By Nicolai Heidenreich

On March 24th this year, it finally looked like debt-laden Osprey Maritime would be given much-needed financial lift under its wings until the tanker markets would create sufficient cash flow to service and pay down debt. Schroder Venture Partners Asia Pacific Fund (Schroder) had offered to invest as much as $54 million as part of a major recapitalisation process which potentially could have raised $70 million. In the same breath, Osprey wrote down book values of their assets by $175.8 million and we felt that with VLCC and product carrier rates on a significant rebound, Osprey was in a good position to not only service current obligations but also to take advantage of opportunities in the market.

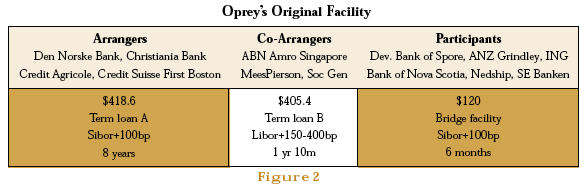

Unfortunately, the deal fell apart. One of the conditions set forth by Schroder was that the deal had to be approved by all senior creditors to the company, i.e. the 14 banks that make up the syndicate for Osprey’s $944 million term loan facility signed July 18th, 1997. One bank refused and the deal fell through. What would this deal have meant for Osprey? How could one bank see so differently on an issue which 13 of their peers agreed on? Was this a case where special credit committees take over from the relationship banker? And most importantly, what now for Osprey? These are a few of the questions left after the stranded deal and we will answer them throughout the article.

Schroder to the Rescue

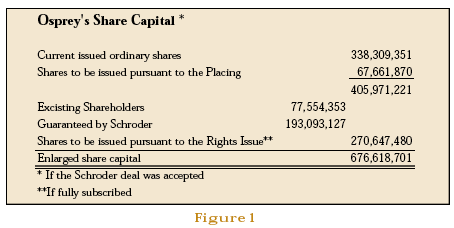

The capital infusion from Schroder was split into two tranches. First, a private placement of 67 million new shares at S$0.35 per share would raise nearly $14 million. Concurrently with the private placement, Osprey would undertake a 2 for 3 renounceable rights issue that would, along with the private placement, increase shares outstanding from 338 million to 676 million (338 m shares + 67 m shares = 405 m shares, 405 m shares x 1.667 = 676 m shares). Schroder would subscribe in full for its entitlement of 45 million shares (67 / 405 x 270 = 45), as well as guarantee a share application of 148 million shares to the extent that such shares were not taken up by existing shareholders. This would raise $40 million above the private placement from Schroder (193 m shares x S$0.35 = $0.60/USD 1), and potentially $16 million more from the existing shareholders. After completion of the deal, Schroder stood to control between 16.9 % and 38.5% of Osprey’s common shares, depending on whether or not the remainder of the rights issue were subscribed to. For a detailed break out of the proposed plan please see Figure 1.

What Did Osprey Have to Offer?

At the time the Schroder deal was announced Osprey was in need of a cash infusion, either through fresh equity, sale of assets or extensions on their balloon repayments. Marine Money estimates that the company’s cash holdings are around $60 million as of June 30th, and with short term debt of around $100 million due in the second half of the year, the company needed money not only to service debt, but also to maintain their ships and participate in current market opportunities. Of the $100 million, $77 million stems from a $90 million prepayment obligation which was part of the extension agreement signed with its banks last year. The company has already sold two ships this year, the 85-built aframax Gita Ayu and the 87-built product carrier Gadis Ayu in January and March this year, which brought around $24.1 million in cash, of which nearly $13 million was used to reduce the $90 million. But with an average EBITDA we estimate that operating cash flow will not be sufficient to service the $91.5 million due in the second half of the year. So why would Schroder put new equity into a company which would be instantly subordinated to $793 million of senior debt. As we see it, the answer is two fold.

Firstly, of the $140.5 million in short term debt due this year, $90 million was a prepayment obligation of one of the company’s term loans. A clause in the Schroder deal required Osprey to remove this obligation, as it was only in place secure the banks’ position after the maturity extension from last year. As mentioned earlier, this obligation was a part of the deal signed in 1999 extending the maturity $362 million of debt until 2002. Although some of the money would go towards reducing debt, the new equity was used to improve the company’s cash position enabling it to take advantage of market opportunities and not just to reduce debt.

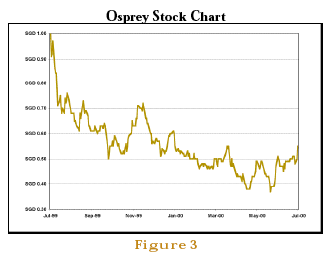

Secondly, on March 24th, the time of the announcement of the rights issue and the private placement, the Osprey shares closed at $0.55 so Schroder was potentially offered 43.5% of the company at a 36.4% discount to its trading price. In addition it was an opportunity for Schroder to buy into a rising tanker market at a great discount to net asset value while Frontline, Bergesen, Teekay, OSG and OMI were all attempting maritime equivalents of dot com performances.

Most importantly Schroder had spent over a year following the company’s business and going through an extensive due diligence process. They visited both terminals and the company’s major customers and found out that the combination of the secured long term revenue stream of over $1 billion combined with the near term upside potential on the crude and product side, Osprey at S$0.35 cents was a clear buy.

Happy Happy Happy

So Osprey and Schroder were of course happy, but what about its creditors and most importantly its shareholders? As Marine Money understands it, Osprey introduced Schroder to its syndicate arrangers in the second half of last year (see below), and the four banks were delighted to see that the company had been able to locate new investors who, at a discount, were willing to take on the Indonesian risk and invest in the company. In addition, not all of the new equity was being spent on acquiring new tonnage or fleet refurbishment which is so often the requirement of new equity investors. In this case, cash would also go towards reducing debt. The bank’s early conclusion was that the existing shareholders would be the cause of concern, as they would be substantially diluted without a corresponding increase in net asset value.

The company then approached its two main shareholders, Bambang Trihatmodjo, son of former Indonesian President Suharto, and the Barclay brothers, who control 41% and 23.5% of the company respectively. As Marine Money understands it, both agreed to the proposal and the four arranger banks only had to convince the remainder of the syndicate and the deal would be signed at the AGM in June. How wrong they were.

Why ABN Said No?

After the four arrangers had been in contact with the main shareholders and participated in the negotiations with Schroder, the banks brought the proposal to the syndicate for approval. The four banks must have thought, which most banks do, that an equity infusion, which secures their position as creditors, is positive and brought the deal to the syndicate with a recommendation stamp. During the numerous meetings that took place in April and May it soon became clear that ABN Amro Singapore could not get the needed approval from Amsterdam and the deal eventually faulted.

What could have caused ABN Amro, a shipping bank with great experience to say no, when 13 banks, of which all but one is a devoted shipping lender said yes?

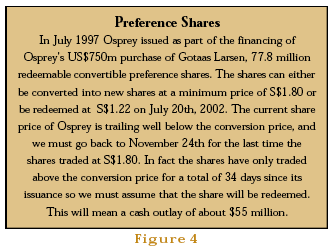

There are several possible reasons. In order for the Schroder deal to go through, Osprey would have had to reschedule the maturity of its $362 million medium term debt until the third quarter of 2004 from July 20th, 2002. The maturity of the debt had already been extended in a deal signed with the banks last fall giving Osprey a three year extension from its original due date of July 20th, 1999. The main issue here is probably not the extension of the principal repayment in itself, but that by doing so the debt would mature after the redeemable convertible preference shares which mature on July 29th, 2002. The preference shares, as described in the box on the next page, will most likely cost the company $55 million and ABN clearly felt more comfortable knowing they would get paid first.

A second possible reason could be that ABN felt that the company was selling itself too cheaply. Why should they take another extension on their balloon payment when Schroder can come in and participate in the upside.

A third reason, could be that since a substantial portion of the debt would be extended until 2004 and more importantly beyond the maturity of the preference shares, another department of ABN Amro stepped in. Although ABN Amro in Singapore, which has the client relationship in this case okayed the deal, the shipping team in Amsterdam with pressure from the special-credit / workout group said no.

This phenomenon is one of the many results of increasing mergers between banks and the subsequent “corporatization”. It is a relatively new territory in shipping but it is something we will see more of in the future. In the US it is more common and has been a part of corporate America for a long time. Tom Wolfe’s recent book “A Man in Full”, talks about Mr. Croker which finds himself demoted from the top floor meeting room at his lenders offices down to a 7th floor room with no view. The banker leading the “how’s your financials” meeting is not his long time friend and relationship banker golf buddy but a junior workout guy from

“special credits” who bets with his colleagues how quickly he can get his “clients” to form saddlebags of sweat under their arm pits. Although saddlebag tactics are not used a lot in shipping there has been an increasing number of instances in the last year. Hvide is probably the best known case in the US where after a lengthy time in financial troubles, its lead banker tightened its screws and forced the company to accept short term facilities with margins close to 1000 points above libor. As Mr. Blankley the former Chief Financial Officer of Hvide said in his speech at this year’s CMA conference, the people that he met when he went to see his bankers were not the friendly face of his loan officer but the banker from the “special asset division”.

Which of these reasons that we have discussed is the right one we are not sure of. What we do know is that the term “syndicate risk” has gotten new meaning for the 13 banks that are involved in the Osprey facility. We would also think that banks would think twice before inviting ABN Amro into syndicates unless they can give an explanation of why they acted as they did.

Solutions

So that covers the failed deal, but what about Osprey? Will they survive without an equity infusion, sale of vessels or a restructuring of debt? Probably not. Even with today’s freight market the company is not generating sufficient cash flow to service their $100 million short-term debt obligations. A solution would be to postpone the repayment of the remaining $77 million of the prepayment obligation. This would however only have a short-term effect since the company has annual debt service of about $50 million and would have additional principal repayments in 2002 in addition to payment to the holders of the preference shares.

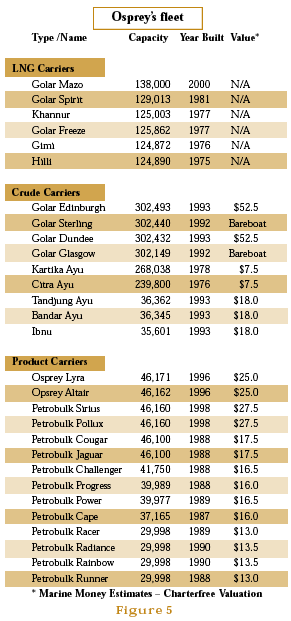

Option two, which we think is the most likely solution is a aggressive liquidation of assets. The company is in possession of very attractive tonnage in today’s market and as can be seen on the accompanied fleet list, which includes MM’s own charter free value estimates, several of the ships can be disposed of above current debt levels. The balancing question is of course will the reduction in annual debt service be greater than the reduction of EBITDA.

A third option which would potentially be suitable for everyone, with the exception of ABN Singapore, is that the arranging banks, DnB, CBK, CSFB and Credit Agricole could get together and take ABN Amro out of the syndicate and to go through with the Schroder deal. We understand the option has been discussed, but we have very little reason to believe that ABN will sell, unless of course the rest of the syndicate makes an offer that ABN’s special-credit group can’t refuse. Par.

Taking away the keys from the company and doing a yard sale would not serve any purpose. The value of Osprey is not in its tankers, although at the moment it may look that way, but locked away on long term contracts with its LNG vessels and to try and sell the ships including the charter without the existing relationship that exists between the company’s management led by CEO and Chairman Mr. Tim Cottew, would not get a bank looking to unlock value anywhere. From a creditor point of view, all are best suited with assisting the company continue as a going concern, but if all else fails, Marine Money has come up with a suggestion of its own.

1. Sell the two remaining VLCCs to Tankers International

2. In the same transaction, OMI sells its Suezmaxes to Frontline

3. Osprey sells its share of IPC, leaving OMI as a pure product tanker player.

4. Raise $500+ million in a bond offering with LNG charter revenues providing healthy EBITDA coverage.

5. Buy back all the company’s shares at a 50% premium on today’s price ($157 million)

6. Pay off all or most outstanding bank debt with the proceeds from the offering and the cash generated from the sale of the vessels.

Just a thought.

Niki Shipping: Adding Value Through Financial Engineering

By Kevin Oates

One of the complaints often lodged against traditional shipowners is that their lack creativity and imagination results in a commoditized business where like assets compete with each other based solely on price. In other words, owners do not add enough value to the process. While it is true that two vessels of the same size and age are not radically different, an area where shipowners can add value is through creative vessel financing structures that serve to maximize efficiency and effectively spread and price asset risk.

In our view, one of the companies leading the charge ahead in this area is Niki Shipping of Greece. Named for the Greek word for victory, Niki controls assets worth more than $500 million yet operates from a small office in northern Athens which houses a lean team consisting of the principal, an accountant, a technical advisor, a legal adviser and a strategic adviser.

Niki currently has an interest in a series of 10 container feeder vessels built between 1979 and 1985, and wholly controls a further five container vessels, two built 1998 with capacity of 2,900 TEU and three built 2000 with a capacity of 5,500 TEU. A further two 5,500 TEU vessels are under construction and due to be delivered during summer 2000. When all the newbuildings are delivered, Niki will control vessels with a capacity of 38,300 TEU and have an interest in other vessels with a capacity of 12,164 TEU. This puts Niki up amongst the big boys, at least in Greece.

Continue Reading